Summary:

This is my book report that I wrote on the book Flatland by Edwin A. Abbott. Here, you can learn about what happens in the book, the context of the book, a short biography of the author, and how this book relates to the philosophy of mapmaking and displaying data visually. In an age where we live in a perpetually expanding ocean of data that will only continue to grow even faster over the years, it has become important to be able to display information visually, and to do so through multiple channels and dimensions. The human brain is overwhelmed with this deluge of data if non-visual, text-based methods are used. People would have to sift through and read the information for hours and hours, and not everybody is cut out for this kind of mental strain. That's where graphicacy comes in-- the ability to decipher information visually through maps, graphs, and charts-- to save the day for us all. Mapmakers and scientists like me work hard to create maps, charts, and/or graphs that convey copious amounts of data and information in a package that's easier for the average Joe to process. And with information and politics becoming more and more overlapped, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, these skills will be critical to life in the 21st century. The book, Flatland contains a key bit of philosophy that explains everything one would need to know about creating these charts and graphs.

Table of Contents:

- About the Author

- About Victorian England

- About Flatland (Setting)

- About Flatland (Story)

- Escaping Flatland

- How Minard's Map Escapes Flatland

- Concluding Thoughts

- Bibliography

About the Author:

Edwin A. Abbott was born in 1838 in Middlesex, which is now a part of the Greater London Area, just as the Victorian Era was getting started. This era lasted through most of Abbott's life and would shape his views of the world, as well as the world he would create later in his life. Educated at St. John's College with a storied career in academics, Abbott dedicated his life to literature, intellectualism, and teaching. Abbott was a highly regarded educational figure, working as the headmaster of the City of London School-- where he went to high school-- from 1865 until he retired in 1889. Afterwards, he dedicated his life to his love of writing and authoring books about the subjects he was most fascinated in. He did not retire due to old age, but rather so he could spend more time pursuing his personal desires, which really began to take shape in the 1870s.

As headmaster, Abbott wrote many books about writing and grammar, scholarly work on Sir Francis Bacon, religion, and literary criticism. But his most well-known work is his 1884 novella Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a book about a square in a two-dimensional world called Flatland visiting and exploring other dimensions, such as a one-dimensional world known as Lineland, a three-dimensional world known as Spaceland, and a world with no dimensions known as Pointland. Abbott wrote the book as a satirical novel that skewered the cultural norms, arrogance, and repressive social codes of Victorian England. Abbott, however, took this to such extremes that the book is thought by some to be a dystopian novel. This would put Abbott as one of the grandfathers of dystopian literature among H.G. Wells, Jack London, and Jules Verne. The book was highly regarded when it was released in 1884, but didn't sell well, and didn't achieve popularity for years. Abbott would die in 1926, hardly knowing if his book would ever make a lasting impact outside of a small circle (O'Connor and Robertson, 2005).

It wasn't until the 1920s that the book began to take hold on culture, thanks to the work of Albert Einstein, specifically the theory of relativity, which opened the possibility of a fourth dimension beyond our own. Today, Flatland is held as a masterpiece of science fiction, as well as mathematical fiction, and has been praised by people we know today like Steven Hawking and Carl Sagan. But the story itself has developed a meaning of its own and has resulted in the phrase "escaping Flatland" being added to our lexicon. Simply put, this refers to our creations on paper and screens being filled with information and data so much so that they become immersive and metaphorically jump out of the paper/screen, like the square from Flatland being pulled out of his two-dimensional world by the sphere, and entering a higher, third dimension beyond his. Flatland, and the phrase "escaping Flatland" has been applied to all kinds of fields that use graphics and map-making to convey information, such as science, mathematics, and geography.

About Victorian England:

The Victorian Era in England lasted from 1837 to 1901, coinciding with the reign of Queen Victoria. During this time, England became a global power, but also underwent dramatic economic and political changes. The First Industrial Revolution had concluded by the time Victoria ascended to the crown, and the Second Industrial Revolution would forever alter the economy of Great Britain and send shockwaves around the world. With the introduction of concepts like mass production, the revolutionizing of the production of steel and iron, significant improvements in agriculture, and the creation of machines like the steam engine, population and economic growth would steadily rise for decades. Railroads were constructed all over the country. Factories, buildings, and a massive telegraph grid spread across the land like wildfire. People would migrate to the big cities in flocks. Massive social change was on the horizon. But Victorian England was culturally conservative, which heavily repressed and prevented any chance of a major upheaval in society of the likes that happened in other countries like France, Italy, Russia, and Germany.

Even though Parliament's responsibilities and power expanded throughout the Victorian Era, its backdrop was a strongly conservative culture. Both the middle and upper classes despised revolutionary violence and held contempt for the political movements that were going on outside of the country, such as Marxism and socialism. The aristocracy of the country would weaken politically, but their grasp on the social aspect of life was still white-knuckle tight. This meant that Victorian England was rigidly organized on hierarchy, mostly by gender and class. Men were strong, were supposed to act strong, were involved in public life and politics, and sex was their purpose in life. Women were supposed to be weak and sensitive, involved in the private life back at the house, responsible for motherhood, cleaning, and religion, and reproduction was their purpose in life. This was all based on the doctrine of separate spheres, of which men and women were forbidden to cross, however sexist it may be. The wealthy and powerful in England held titles, owned most of the land in the country, and presided over politics with an iron fist (Steinbeck, 2022). The middle class would make considerable gains in power over the years, but the aristocracy fervently held on to whatever power they had left. The lower class was all but shut out of politics, and lived and worked in brutal, unsanitary conditions. Even children were subject to the brutality of industrial work at the time. However, class mobility was higher than one would think based on the description given of society, which ultimately prevented a violent upheaval that happened elsewhere around the world.

One could say that Victorian England was an extremely judgmental society. It is worth noting that Anglican Church held unquestionable moral power in England at the time. Every class viewed each other with strong disdain somehow, often through the lens of religion, especially if one was of a lower class than them. The lower class were viewed as dirty, expendable, uncultured, and hostile to intellectualism by the middle and upper classes. At the same time, though, Victorian England as a society a whole was closed-minded, and refused to entertain the more liberal ideas that spread in the rest of Western Europe at the time. The upper and middle classes got along somewhat amicably through work, but the lower class despised the upper class, thinking of them as pompous, obnoxious, and controlling. The lower class also wasn't fond of the middle class, angry at their mobility in society that the lower class didn't really have. Dress codes were very strict, prim and proper, and modest. To have stained, torn, revealing, or baggy clothes was to be seen as a piece of trash. To have a physical deformity was to be seen as an abomination to God, and breaking the rules of nature (Falk, 2012). These types of behaviors have created stereotypes of British people, aristocracy, and the monarchy that persist today.

About Flatland (Setting)

Flatland is the titular setting of the book Flatland and serves as the main setting for the book. Everybody lives in a two-dimensional world upon a flat, planar surface. All its inhabitants are geometric figures with "eyes" to see. The first half of the book is set aside for describing the environment of Flatland and all its inhabitants. In the book, the women are line segments and the men are polygons of differing amounts of sides from triangles and squares to octagons, all the way to circles. All the inhabitants of Flatland can move freely about their daily business, but they can't move three-dimensionally like we can. In other words, think about the magnets on your refrigerator if they could move along the surface of the refrigerator doors, but if they were permanently stuck to the door. The only way the magnets could move is along the surface. This goes for the inhabitants of Flatland.

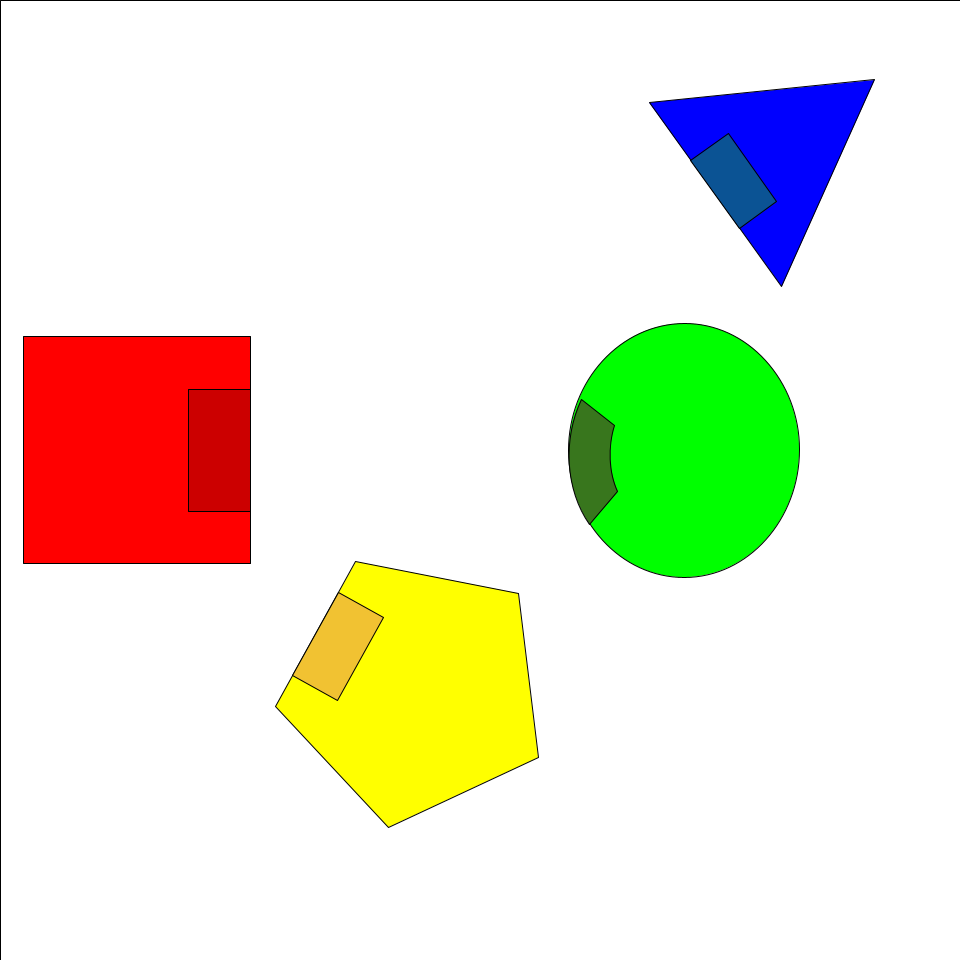

They also cannot see three dimensionally like we can. The inhabitants of Flatland can only see in lines. To get the picture, "[p]lace a [coin] on the middle of one of your tables in Space... [and] gradually lower your eye... [until you are] exactly on the edge of the table..." (Abbott, 1884). Flatlanders cannot look up or down like we can, only left or right. Because the inhabitants of Flatland cannot see in a higher dimension than their own, they are hopelessly ignorant of the concept, and even hostile towards it. They cannot see it, and it is impossible for any of them to comprehend it, therefore it does not exist and is not worth the time to even consider it. A Flatlander's sense of depth and perspective is severely hindered compared to three-dimensional beings like us, since they cannot see height. They compensate for this by using brightness. Closer objects to the subject's "eye" are brighter. Notice how in the diagrams to the right, the yellow pentagon is the closest to the red square's "eye". The pentagon will appear the brightest to the square, and therefore, is the closest to the square. However, a Flatlander would be incapable of comprehending the drawing above the one to the right, since they cannot physically see from the top down. How would one tell a circle apart from a square from a pentagon, and so on? They cannot see angles like we can, so they use something in their world called "Fog" as one method to tell each other apart. In a triangle's case, its sides would quickly recede into the Fog, while a pentagon's sides would not recede as quickly (Abbott, 1884). You could say that triangles would appear as shorter line segments to the inhabitants of Flatland than squares, who are shorter than pentagons, and so on. Even so, sight is very difficult for Flatlanders, making it art form that the upper class is the most skilled at. Flatlanders can feel each other, however, of which the lower class takes advantage of.

Flatland has an extremely rigid class structure with very little social mobility, practically making it a caste system. The more sides you have as a geometric figure, the higher up you are in this system. Women are automatically placed at the bottom of the system, since all women in Flatland are lines, a depiction of how repressed by sexism and misogyny women in Victorian England were. Because women were sharp and pointy enough to stab the male Flatlanders, they are required to make a "peace-cry" (Abbott, 1884) at every single instance they were present somewhere. They are also required to wiggle as they move to prevent them from looking like a point to the men, a form of objectification. The men in Flatland are extremely paranoid about the women and what they could do if they were to obtain any power in society, so they put them in a stranglehold of rigid sexuality, sexism, and oppression. Triangles are higher than women, but are still towards the bottom of Flatland's society. They are tasked with the dirty jobs of the world, and are viewed as the most expendable. They are also divided between Isosceles and Equilateral, of which the latter is higher than the former. Squares are higher than triangles and serve as the gentlemen class of Flatland. All of the polygons in Flatland (pentagons, hexagons, octagons, etc.) are part of the upper class of Flatland, and are responsible for running the churches, schools, businesses, and government. The circles are at the pinnacle of Flatland's hierarchy and are the ruling class. They are absolute monarchs and have unquestioned power over the inhabitants of Flatland.

As mentioned before, social mobility in Flatland is virtually non-existent. As a result, there are "[hundreds of] other details of our physical existence" (Abbott, 1884) that the narrator doesn't even have the time or patience to talk about. In other words, there are hundreds, if not, thousands of rules, legal and social, that almost completely prevent any and all class mobility within one generation. Every time a male is born in Flatland, he will have one more side than his father. For a son, a triangle will have a square, a square a pentagon, a pentagon a hexagon, and so on. Circles have an infinite number of sides, so it would take several generations for a family of triangles to have even one circle. One way the triangles and squares tried to exploit how Flatlanders see was to use color to make one think that they have more sides than they actually do. As a result, all color is forbidden in Flatland. Color is used in the diagrams on this page for our own sake (the three-dimensional beings). Another way polygons could have upended the caste system by appearing to have more sides than they really do is through irregular shapes. But any polygon in Flatland that is born with an irregular side is placed under constant surveillance, may have their side forcefully made regular, or even put to death to keep the caste system intact. This is similar to how in Victorian England, people with physical deformities were viewed as affront to God. But Victorian England had more class mobility than Flatland does, but the social structure of the former was still very rigid. However, the lower class of the former probably believed their country's social structure resembled the latter more. Unlike Victorian England, though, the inhabitants of Flatland, for the most part, are dedicated to preserving the universe's social structure, and are practically brainwashed to be hostile towards other ideas, other beliefs, and especially other dimensions.

About Flatland (Story)

(imgflip, 2014)

The main story of the book begins in the second half of the book. It starts shortly before New Year's Day in the year 2000, based off of the universe's calendar. Our main character is a square whom we'll call the Square. While the Square is sleeping, he dreams of visiting a one-dimensional world called Lineland and tries to convince their inhabitants of a higher dimension. They take offense to this suggestion, and end up executing the Square in response. When the Square wakes up, he is visited by a Sphere from Spaceland. The inhabitants of Spaceland are solids that live in a three dimensional world, exactly like the world that you and me inhabit. Spaceland's inhabitants can move unimpeded throughout their universe, and are capable of seeing and comprehending depth. To the inhabitants of Flatland, however, they look like what is displayed in the animation to the right. Imagine the beige-colored surface is Flatland, and the green sphere is the Sphere from Spaceland. You will see what he looks like to the Square as he passes through Flatland. At every turn of the millennium, the Sphere visits Flatland as an apostle, in an attempt to convince the inhabitants of Flatland of a third dimension. The Square, however, is not impressed by this display. So the Sphere takes the Square out of Flatland, and into the third dimension.

The Square is astonished by what he sees in Spaceland. The Square can now see all of Flatland on a plane, and watch everything going on in the universe. He can see that a trial is going on in Flatland that is held every millennium against those who claim to have any sort of knowledge or vision of a higher dimension, not unlike the Salem Witch Trials in our world. Any shapes found guilty are eternally imprisoned or sentenced to death. The Square recognizes his brother at the trial, and tries to jump back into Flatland and convince him of Spaceland's existence. The Sphere follows him, and descends into the courtroom to proclaim the existence of a third dimension to the inhabitants of Flatland. The Circles are offended by this display, and declare the Square and Sphere to be heretics. They are forced to run away from Flatland before they are arrested. Simply for witnessing this spectacle, the Square's brother is arrested.

Back in Spaceland, the Sphere tries to introduce the Square to his three-dimensional counterpart, the Cube. The Square now questions if there is a fourth dimension beyond that of Spaceland, which offends the Sphere greatly. Disgusted by his impudence and constant questioning, the Sphere kicks the Square out of Spaceland and back into Flatland. Once there, the Square tries to enlighten the denizens of Flatland about what he saw in Spaceland, and the concepts of a third dimension. The Square starts working on a memoir about the third dimension, which turns out to be the book Flatland of which we are reading. Yes, the entire book of Flatland is a memoir written by the square. As the Square tries to spread the word of his book, and enlighten Flatland about a third dimension, he is arrested and sentenced to eternal imprisonment by the Circles. The Square will spend the rest of eternity imprisoned, to prevent his knowledge of Spaceland from ever disseminating, and to eliminate even a scintilla of a chance of any sort of revolution or upheaval that would destroy the class structure of Flatland. The Square will never be able to spread his word and convince others of a higher dimension, but he leaves that work up to you, the reader.

Escaping Flatland:

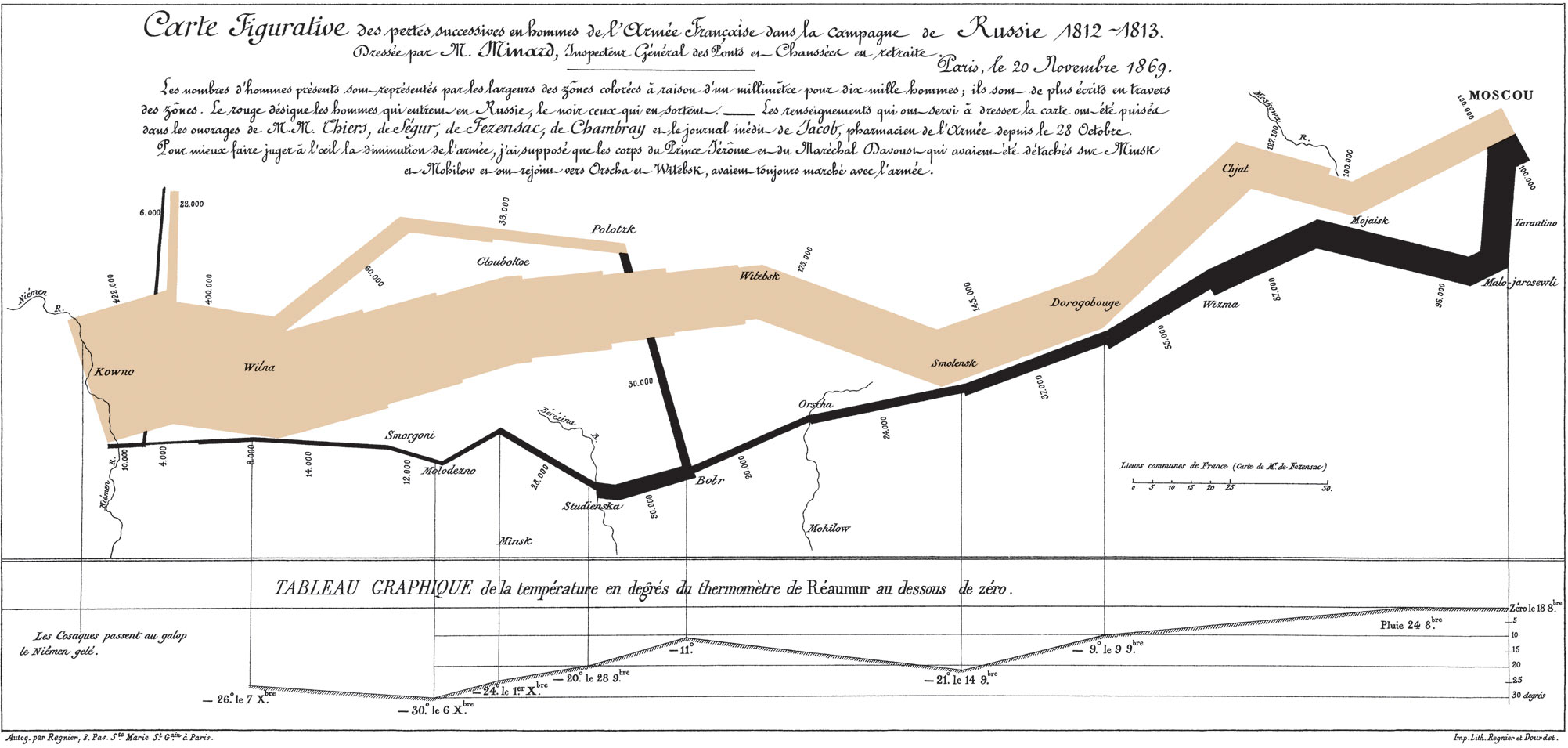

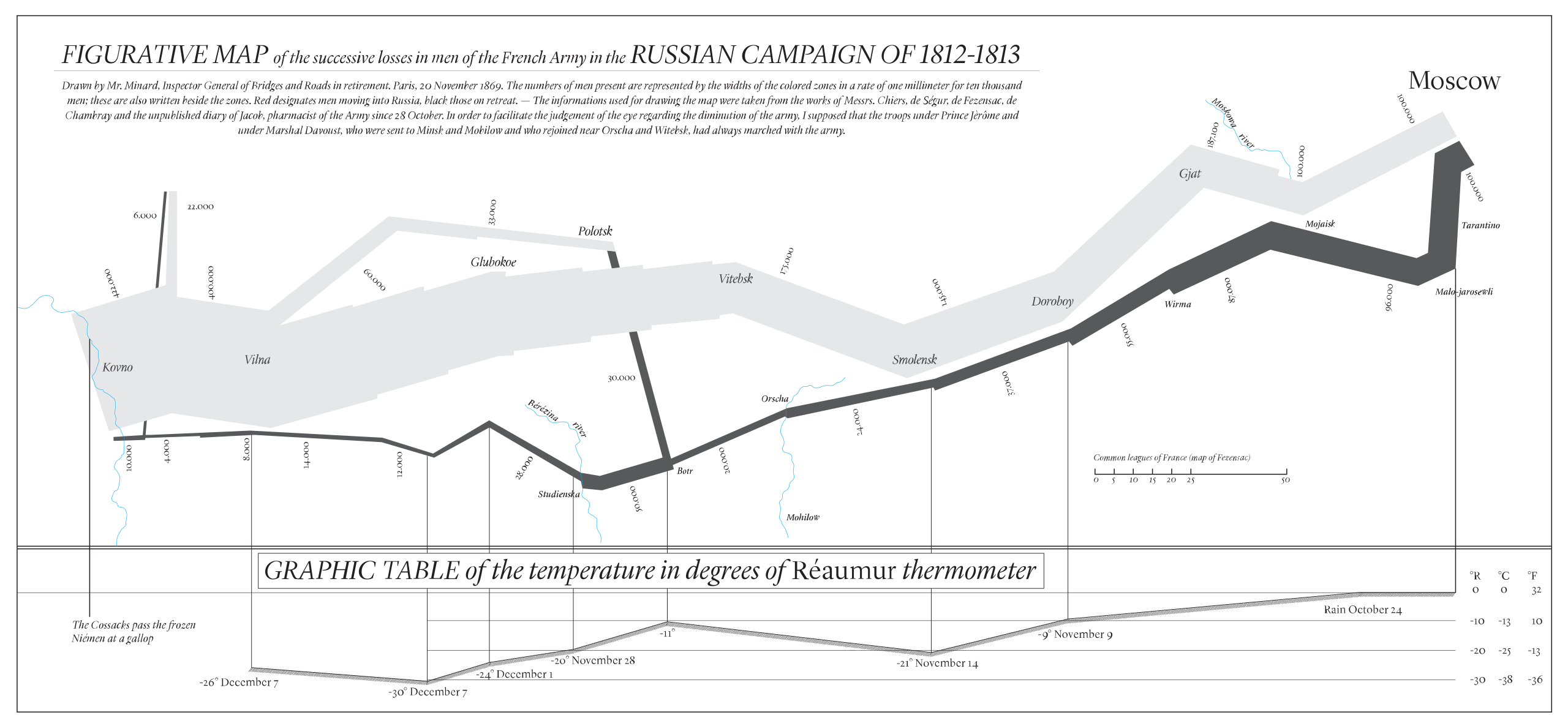

So what does it mean to escape Flatland? It depends on what context one is thinking of. Because the phrase "escaping Flatland" can be applied to several different fields of science. If one were to do a search "escaping Flatland" through a search engine such as Google or Bing, one would find results relating to medicine, journalism, and even art. But they all have one common definition created by Edward R. Tufte, a professor of statistics and data at Yale University. According to him, "[escaping] Flatland is the essential task of envisioning information...". What does this mean? Tufte further elaborates by saying that to escape Flatland, one must "increase (1) the number of dimensions that can be represented on plane surfaces and (2) the data density (amount of information per unit area)" (Tufte, 1990). But this doesn't answer the question completely about what it means to escape Flatland. Who is escaping Flatland in this situation? And what does this have anything to do with cartography and map making? The answer: if your maps escape Flatland, they will be so rich with dimensions (different forms of information in this context) and information that the map becomes immersive and their concepts more tangible to the viewer. In other words, the maps may seem to be jumping out of the paper they're printed on or the screen they're displayed on, like how the Square is able to escape the planar world of Flatland and into Spaceland. Maps that successfully escape Flatland are rich with information, and are immersive to viewers. One of the finest examples of maps that successfully escape Flatland was created in 1869 by French civil engineer Charles Minard, depicting Napoleon's ill-fated invasion of Moscow in 1812.

What does this picture mean? For starters, the beige-colored band stretching across the map from left to right represents Napoleon's troops on the march. His attempted invasion of Moscow began at the Nemen River near the town of Kovno, in what is now Lithuania. Also displayed on the map is the number of troops present at each point of the invasion. Napoleon's army started out with an estimated 450,000 troops. Along the way, the invading forces split up into two battallions to occupy what is now Riga, Latvia and Minsk, Belarus (the battle took place in the nearby town of Gorodechno). But as the army advanced deeper into what is now Belarus and then Russia, troops fell ill, supply lines began to break down, and the army encountered fierce resistance from the locals. Napoleon's army began to quickly thin out from disease, desertion, and attacks from the locals. In accordance to this, the beige band becomes thinner and thinner leading up to Moscow. By the time Napoleon's army finally reached Moscow, it had shrunken to 100,000 troops from 450,000. Napoleon was able to put Moscow under his occupation, but it only lasted for shortly more than a month. And during this time, Cossack soldiers put up fierce resistance to his army through guerilla warfare. Afterwards, Napoleon's army was forced to retreat to avoid being surrounded and attacked. The retreat is marked on the map by a band in black. And that's when the brutal Russian winter set in. On the bottom of the map is a graph of temperature connected to each point on the map. For instance, as the retreating army reached Smolensk, even more troops had froze to death from the cold, which was reaching -21° Réamur. To convert Réamur to Celsius, you take the temperature in Réamur and multiply it by 1.25 or 1 and ¼. In this case, when the retreating army reached Smolensk, the temperature was about -26° Celsius or about -15° Fahrenheit. Napoleon's army had shrunken to less than 37,000 troops by now. Passing by Minsk and Riga, the troops occupying those areas also began to retreat as well, and were also thinned out by the winter weather, which got even worse, with temperatures plunging to -30° Réamur (-37.5 °C or -35.5°F). By the time the defeated army made it back to the Nemen, where the invasion started, only 10,000 troops or so were left. Estimates were not well kept in the early 19th century, but it is known that hundreds of thousands of troops died on the way to Moscow, and on the way back. This would destroy Napoleon's aura of invincibility, and mark the beginning of the end of his empire.

How Minard's Map Escapes Flatland:

Charles Minard's map is able to escape Flatland through the copious amounts of information is able to depict on just one piece of paper, of which it has been lauded by geographers and cartographers for. His map has been praised over the years for depicting six types of data across two dimensions: the number of troops, position (and thus, latitude and longitude), distance travelled, temperature, direction of travel, and date. For helpful reference, Wikipedia user Inigo Lopez Vazquez modernized Minard's map and even translated it into English.

As mentioned before, this map depicts the number of soldiers in the invasion by placing numbers at specific points in the invasion, as well of the width of each band. According to Minard's map, translated into English, 1 millimeter of width on the bands equal 10,000 troops (Minard, 1869). Latitude and longitude can be deciphered from locating real life geographic features depicted on the map, such as the Moskva River, as well as cities like Minsk, Moscow, and Vitebsk. Distance on the map is shown on a ruler in leagues (1 league is about 3.45 miles). Temperature is depicted on a map below, and the dates are also attached to data points on this graph, corresponding to the retreat. The retreat began on October 24th, and lasted into December. With all this information, it's hard not to imagine yourself as a part of Napoleon's invading army, as if you were actually there. This is how Minard's map is able to escape Flatland, by making it seem so real, the map and its information almost seem to jump right out of the page, like it's escaping Flatland and spreading out into your world. Good mapmakers create immersive maps capable of channeling copious amounts and channels of data into the viewer's mind without overwhelming them. And due to the tsunami of information and data that has enveloped us with the rise of computers and the digital age, it is more important than ever for maps to escape Flatland. One day, it may almost literally do so through the use of holograms.

Concluding Thoughts:

This book was not an easy read for me at first, and to be honest, it was a bit hard at first to keep my interest while I was reading Flatland for my class. But after a little bit of research, browsing the web for explanations and other stuff, my opinions on this book have taken a turn for the better. It's not an easy book for anyone to read, but being able to understand the meaning behind the book is worth it in the end. I was able to grasp the concept that this book was satirizing Victorian England, but I think it satirizes another part of history even better: the Puritan era of New England. In the early 1600s, as English colonists were moving into what is now Massachusetts, a sect of Protestants known as Puritans were moving in along with them. After the Anglican Church was founded in 1534, separating England from the Roman Catholic Church, some people believed that this movement didn't go far enough, and that the church was still tainted from Catholic influence. The Puritans wanted to eradicate all traces of Catholicism in the English church, and settled in colonies across the Atlantic to create their utopia. It ended up being a nightmarish theocracy, rife with persecution. Puritans were extremely intolerant of religious dissent, did not believe in freedom of speech or the press, and would retaliate with violence. Anyone accused of witchcraft or religious dissent were arrested, publicly humiliated, and often executed. This violence reached its nadir with the Salem Witch Trials in 1692 and 1693. Across the pond, Puritans were the dominant religion in England from the Second Civil War until the Restoration, and witch trials happened there too, but not quite as fervently as in Massachusetts. This would end with the Toleration Act of 1688 in England, and would influence the writing of the First Amendment back in the United States about a century later.

At the same time as Victorian England, there was another movement that was making waves through English culture: Romanticism. This movement was in response to the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment, and represented a longing for the past that had been long gone, a return to the way life was before the 18th century. Romantic authors like William Wordsworth, John Keats, and Lord Byron were popular in England during Edwin Abbott's childhood and into his early adulthood years. Evidently, by the depiction of his world of Flatland, Abbott was not a fan of Romanticism either. I would argue that Flatland isn't just a satire of Victorian England, but of the Puritan Era, and Romanticism. Chapter 18 of this book is what stuck with me the most, and is what shaped my opinion of the book that I am currently sharing with you. Just the idea of the Square's brother being arrested for simply witnessing a sphere really reminded me of a witch trial. This scene was a demonstration of the zealotry of the Circles and Polygons in how insistent they were of maintaining the power structure of Flatland. It was this kind of zealotry and repression that also made me think of dystopian novels like 1984 by George Orwell, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, and Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. Though there was no Big Brother, memory holes, or telescreens in Flatland, the inhabitants of the world exhibited the same kind of brainwashing that the citizens exhibited in the book. In a way, you can say that the Square is made out of the same mold as Winston Smith. I also was reminded of Fahrenheit 451 by the intolerance each of the shapes exhibited for different ideas that would require them to think beyond what they are capable of, namely, the existence of a higher dimension than them. Though the residents of Flatland did not have firemen to burn books, they still chose to swiftly arrest the Square, except he wasn't able to escape like Guy Montag was. And the class structure of Flatland reminded me of the class structure that existed in Brave New World, even with the subsets of triangles (Isosceles and Equilateral) being like each caste of Brave New World's being split into plus and minuses. But unlike Brave New World, the caste system of Flatland had some sort of mobility, albeit very slow, while the former's had absolutely no mobility whatsoever. Some scholars claim that Flatland is among the first dystopian novels ever written, a claim of which I would agree.

In conclusion, Flatland is a difficult, but ultimately rewarding book to read. I do believe that the book effectively satirized Victorian England, but also skewered the Puritans in the process, and serves as one of the first dystopian novels ever written. It took me a bit of time to process, but I was surprised at how literal the meaning of escaping Flatland really was. I would never have guessed before I took this course that escaping Flatland simply meant making maps so detailed and full of information that they metaphorically jump out of the page by being so immersive. I would have guessed a much more complicated explanation, but I guess I overthought things this time. And now that I think of it, it really is imperative that maps and charts are able to escape Flatland. The 21st century will be defined by an ocean of information and data that is growing exponentially as we speak. Without graphicacy and leaving the maps trapped in Flatland, we will surely drown in this ocean of information, and resort to disinformation and propaganda. Unfortunately, this is quickly happening all around us as we speak with the advent of Trumpism and anti-intellectualism tightening its grasp on the American mind. Scientists are having great difficulty in recent times being able to convey their grandiose experiments and research to the public, which has presented opportunities for snake oil salesmen to take advantage of people, as we've seen with the anti-vaxx movement that really gained steam during COVID-19. Thankfully, improving one's sense of graphicacy, as well as the other senses of knowledge (numeracy, literacy, articulacy, etc.) will be valuable tools in combating disinformation that is being thrown at us on a regular basis, and creating maps that can escape Flatland will only aid us further in navigating the ocean of information that will only continue to grow as the 21st century rolls on. Creating quality maps, graphics, and visual representations of data could actually save millions of lives one day. Maybe then we can escape from the Flatland of our minds, and into the world of knowledge.

Works Cited:

- 1880. Portrait of Edwin A. Abbott. [image] Available at: "https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Foto_E._A._Abbott.jpg"[Accessed 21 September 2022].

- O'Connor, J. and Robertson, E., 2005. Edwin Abbott Abbott - Biography. [online] Maths History. Available at: "https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Abbott/" [Accessed 21 September 2022].

- Bassano, A., 1882. Portrait of Queen Victoria. [image] Available at: <"https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queen_Victoria_by_Bassano.jpg"> [Accessed 21 September 2022].

- Steinbach, S., 2022. Victoria | Biography, Family Tree, Children, Successor, & Facts. [online] Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: "https://www.britannica.com/biography/Victoria-queen-of-United-Kingdom" [Accessed 21 September 2022].

- Falk, V., 2012. Fear and Loathing in Nineteenth-Century England: Monsters, Freaks, and Deformities and Their Influence on Romantic and Victorian Society. [online] Seton Hall University. Available at: "https://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2830&context=dissertations" [Accessed 21 September 2022].

- Sphere passing through flatland. 2014. https://imgflip.com/gif/8dxvn [Accessed 22 September 2022]. No official title, author unknown

- Abbott, E. A. 1884. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. United States, New York: Dover Publications. This copy by Dover Publications was first published in 1992.

- Tufte, E. R. 1990. Escaping Flatland. In Envisioning Information, 12–35. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

- Minard, C. 2008. Charles Minard's Map of Napoleon's Invasion of Moscow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png [Accessed 23 September 2022]. This map is now in the Public Domain due to age. It was originally published in 1869.

- Vazquez, I. L. 2015. Redrawing of Minard's Napoleon Map. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Redrawing_of_Minard%27s_Napoleon_map.svg#file [Accessed 23 September 2022].